- The Kerinci Seblat Tiger Protection & Conservation project, led by Fauna & Flora in collaboration with stakeholders, has successfully protected Sumatran tigers in their natural habitat.

- Recent surveys identified a thriving population of 128 Sumatran tigers in Kerinci Seblat National Park, the largest on the island, showcasing the project’s significant impact.

- Despite challenges, such as reduced patrols, the project has decreased human-tiger conflicts, enforced wildlife protection laws, and offers hope for the continued survival of these endangered tigers in the wild.

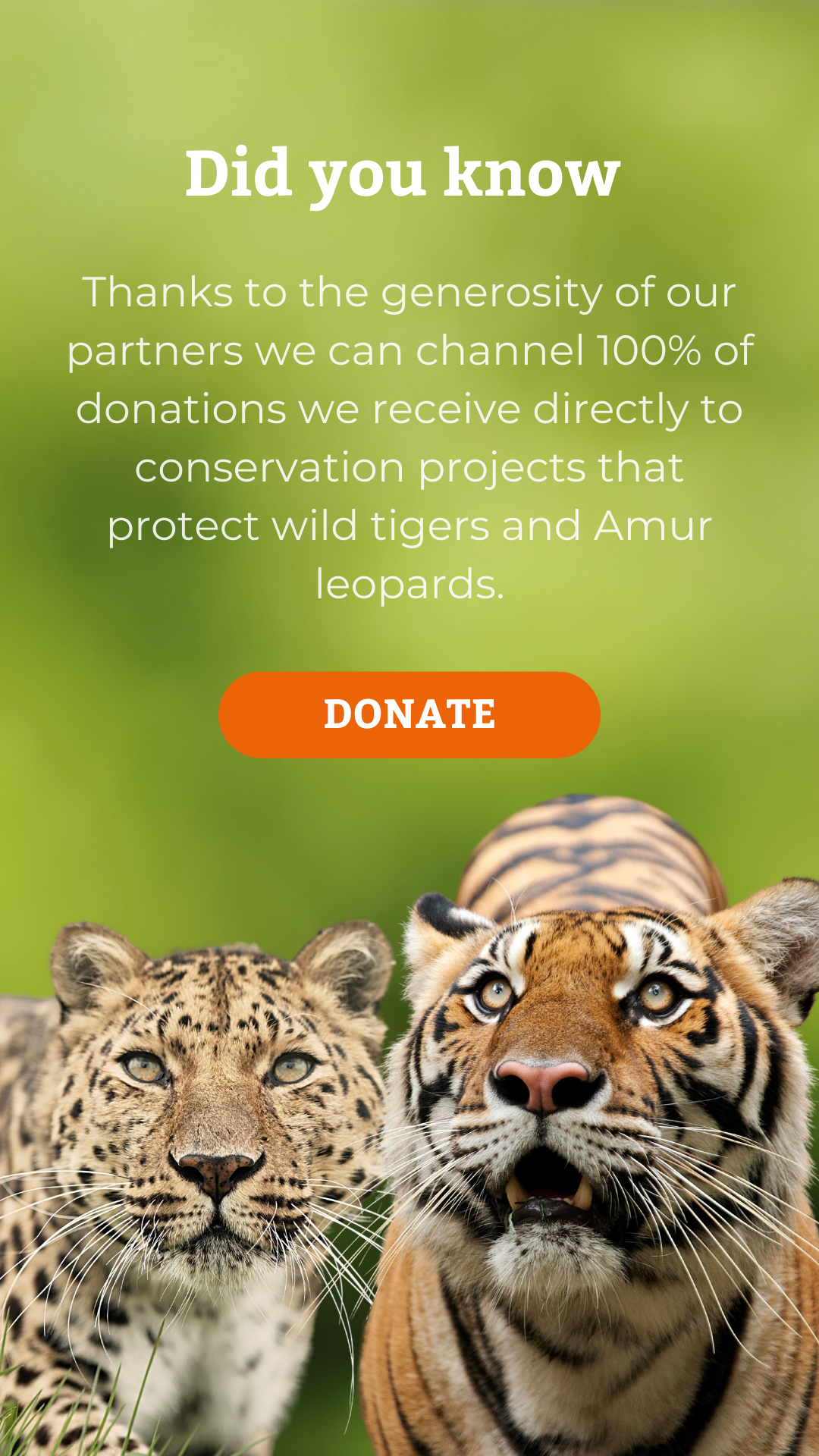

In the heart of Sumatra, Indonesia lies a hidden treasure – the Kerinci Seblat National Park (KSNP). This vast expanse of wilderness, covering 1,386 million hectares (excluding buffer zones), is home to one of the most iconic and endangered big cats in the world: the Sumatran tiger. But these majestic creatures face numerous threats. Habitat loss, prey depletion, human-tiger conflict, disease, and poaching are all contributing factors in pushing this subspecies of tiger to the brink of extinction. That is where the Kerinci Seblat Tiger Protection & Conservation project, led by Fauna & Flora, comes into play.

A Strong Partnership for Conservation

This remarkable project has operated under a partnership between Fauna & Flora Indonesia Programme (FFIP) and the Ministry of Environment and Forestry (MoEF) since 2000. Since its inception, it has been a beacon of hope for Sumatran tigers and is a testament to what can be achieved when organisations work together.

The project’s reach extends from the very core of KSNP out to the edge of the buffer-zone forests surrounding the national park, impacting an area of approximately 350,000 hectares. A project of this scale requires collaboration from various stakeholders, from National Park officers and local communities to academic institutions, all dedicated to

The tigers of Kerinci Seblat

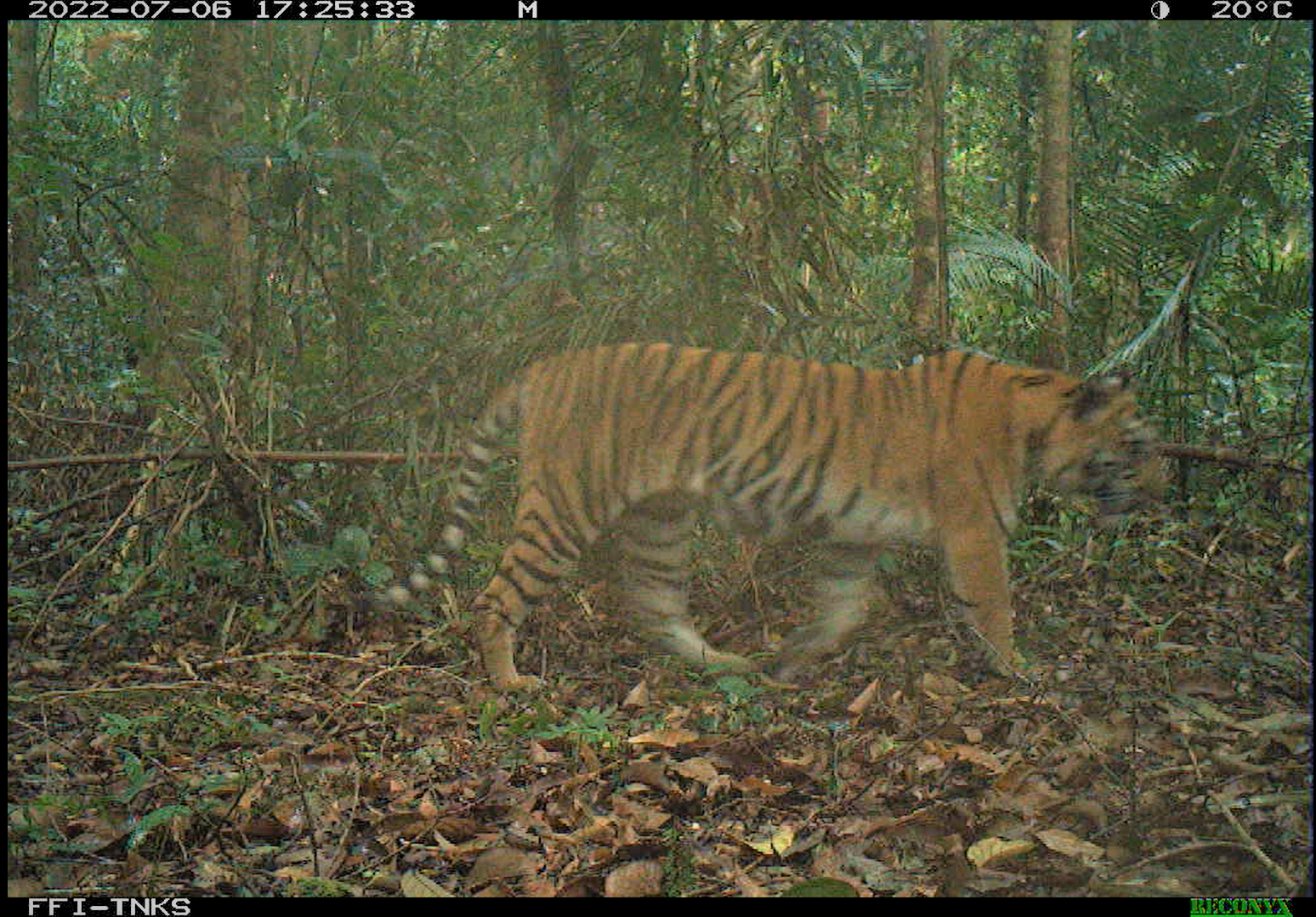

The heart of any tiger conservation effort is data to inform decision-making. The project’s team meticulously surveyed the park in 2019-2020, using camera traps and occupancy surveys to estimate the tiger population. Their findings were nothing short of astonishing – Kerinci Seblat NP and adjoining forests provide a home to 128 Sumatran tigers, with 119 within the park itself and 29 in the Tiger Core Area. This marks the single-largest population of Sumatran tigers on the island, a beacon of hope for this endangered species.

Patrolling summary for the first half of 2023

Effective protection at conservation sites depends on high-quality ranger-based data collection therefore one of the project’s core activities is patrolling using the Spatial Monitoring and Reporting Tool (SMART).

SMART is an open-source combination of software, training materials, and patrolling standards to help conservation managers monitor animals, identify threats such as poaching or disease, and make patrols more effective. It enables rapid access to patrol routes, wildlife signs, locations of sick wildlife, and illegal activities such as a suspected poacher camp with pinpoint accuracy. Data is standardised and can be used to create maps and reports to help managers decide on appropriate actions to take, how to prioritise limited financial or staffing resources, and track changes in activity over time.

The patrols of KSNP and its buffer zones are conducted by the Tiger Protection & Conservation Units (TPCUs). Unfortunately, due to wider national-level administrative issues and the tragic death of two rangers in August 2022, patrol capacity was impacted in the first 6 months of 2023. Nonetheless, the team still managed to conduct 39 SMART patrols covering a total walking distance of 510 miles.

Patrol highlights:

- Interestingly, despite concerns about the resurgence of illegal wildlife trade following the easing of COVID-19 restrictions in 2022, no active tiger snares were recorded during this period. This is a testament to the effectiveness of the project’s strategies and local knowledge networks.

- Poaching pressure on deer remained low with only 10 deer snares destroyed and the remains of 37 recently dismantled or abandoned snares recorded. Anecdotal evidence suggests some poachers are now making use of illegal firearms instead of snares to hunt deer but there is no substantial evidence that this is a significant contributor to the reduced snare poaching recorded.

- The holy month of Ramadan has historically created a local market-driven spike in poaching pressure on deer. However, for the second consecutive year, no active deer snares were recorded during this period.

- All patrols conducted in the Tiger Core Area of the national park reported one or more tigers demonstrating an improvement in the detection of tigers from last year.

Human-tiger conflict

In both the east and west of the protected area, the number of conflicts reported appears to have reduced significantly from the levels recorded between 2021-2022. It is strongly suspected that this may be a consequence of a gradual recovery in wild boar populations which has been reported both by local communities and on TPCU patrols since mid-2022 following the severe mortality among wild boar reported in 2021 due to African Swine Fever.

TPCUs conducted human-tiger conflict mitigation in three cases during this project period, all relating to one-off predation of semi-feral farmland guard dogs moving freely at night and not kennelled. In all these cases, mitigation included counselling farmers and local villagers on tiger behaviour and safety precautions which may be taken when a tiger is or has been, in the vicinity and conflict prevention measures such as livestock management. Villagers in the conflict sites were generally supportive and helpful and the tigers in question appear to have moved on and back into the forest following the incidents, with post-conflict monitoring advising there had been no attempt to exploit these incidents by poachers.

In the southwest of the national park in Bengkulu, TPCUs also provided backup to catch a tiger believed responsible for multiple cattle predations in forest-edge palm oil farms belonging to members of local communities. The tigress was finally caught and found to have an old snare injury resulting in the loss of the lower part of one forelimb. This tigress had been previously photographed during camera trapping in a nearby forest restoration concession. These images and a closer examination determined her injury is old and likely caused by a snare set for wild boar and not for tiger. It was concluded she had commenced predating cattle in response to a sharp fall in wild boar populations due to African Swine Fever. She is now under rehabilitation pending release.

Looking ahead

Despite obstacles, the project’s successes are undeniable. Human-tiger conflicts have decreased, possibly due to the recovery of wild boar populations following African Swine Fever. Law enforcement efforts led to the arrest and sentencing of wildlife criminals, sending a clear message that poaching will not be tolerated. And, despite reduced capacity, the patrol teams demonstrated an impactful presence in the park.

The Kerinci Seblat Tiger Protection & Conservation project is a shining example of what can be achieved when dedicated individuals and organizations come together to protect our planet’s most magnificent creatures. As they continue their work, there is hope that the Sumatran tiger population will thrive in this incredible wilderness for generations to come.