Could this be the first successful reintroduction of tigers anywhere in the world?

Tigers, once roaming vast territories across Asia, are now confined to only a fraction of their historic range. In Cambodia, the last confirmed sighting of a wild tiger was in 2007, and the species is now considered functionally extinct in the country. For many, the possibility of bringing tigers back to Cambodia sparks hope for reversing the decline of this iconic species. However, like any large-scale conservation initiative, reintroducing tigers is a complex endeavour that requires careful consideration of both the benefits and challenges.

Tiger Reintroduction Timeline

The Central Cardamom Protected Forest was the first area formally protected in Cambodia, establishing a base for future conservation efforts.

The last confirmed sighting of a wild indochinese tiger in Cambodia occurred in 2007, in the Cardamom Rainforest Landscape. After this, tigers were declared functionally extinct in the country due to rampant poaching and habitat loss.

The Southern Cardamom National Park was gazetted, securing over 400,000 hectares of vital habitat. Cambodia’s government endorsed the reintroduction of tigers as part of the Cambodia Tiger Action Plan (CTAP), marking the start of efforts to bring tigers back to the country.

A major milestone was reached when India and Cambodia signed a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) to facilitate the reintroduction of tigers. This agreement marked the official beginning of efforts to source tigers from India and reintroduce them into Cambodia’s protected areas.

The first group of tigers was expected to arrive in Cambodia by the end of 2024. India plans to translocate one male and three female tigers into a specially prepared section of the Cardamom rainforest, where they will acclimatise before being fully reintroduced into the wild.

If the project goes smoothly, 12 more tigers will be imported over the next five years.

A 4km x 4km Tiger Reintroduction Center was built over the last year with the latest technology and enclosures for tigers. Image courtesy of Global Conservation

Where will they be reintroduced

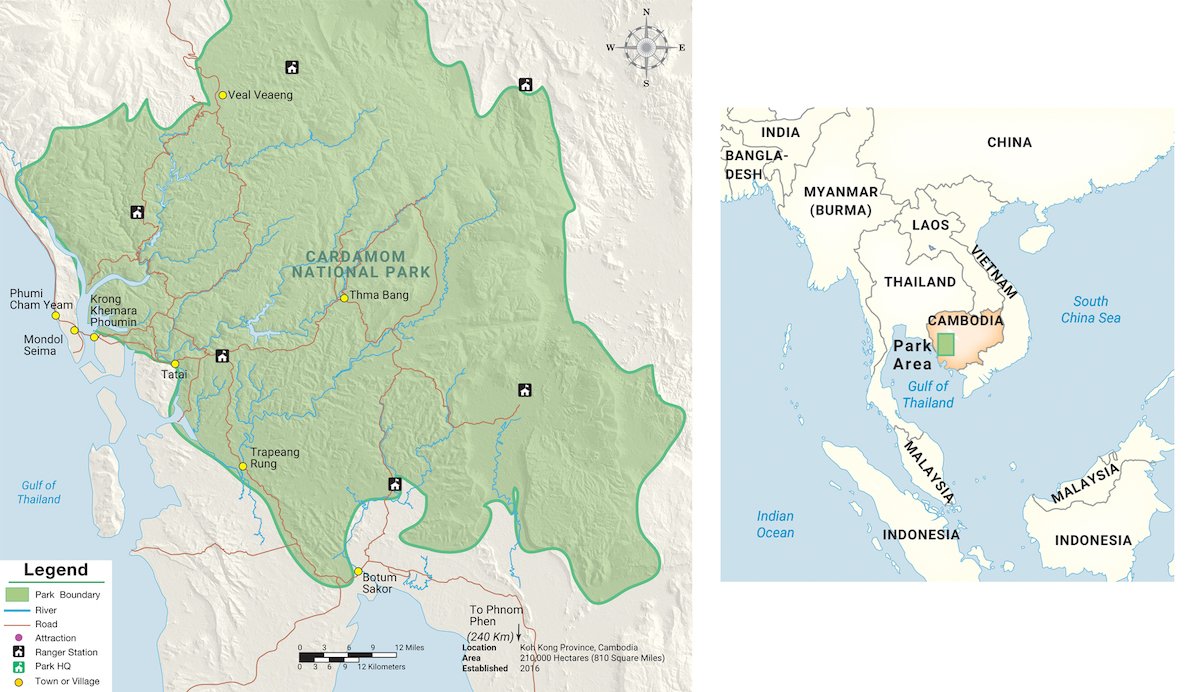

In the aftermath of the Cambodian Civil War, the Cardamom Mountains which were isolated from development and exploitation for many years faced widespread destruction from logging, poaching, and slash-and-burn agriculture as communities sought to rebuild their lives. Despite this, the regions that remained untouched have become some of Southeast Asia’s most pristine wilderness areas.

In response, international conservation organisations began working with the Cambodian government in the early 2000s to protect the landscape. The creation of the Southern Cardamom National Park in 2016 was a key step in securing the area which is now one of Southeast Asia’s largest intact rainforests.

The park spans over 800,000 hectares, encompassing dense monsoon forests, melaleuca wetlands, mangroves, and a network of rivers and estuaries flowing into the Gulf of Thailand. This fragile ecosystem is home to endangered species like Malayan sun bears, elephants, gibbons, clouded leopards, and Sunda pangolins. Although tigers haven’t been seen in the area for some time, it has been identified as the location for tiger reintroductions within Cambodia.

© globalconservation.org

The Case for Reintroducing Tigers to Cambodia

- Restoring an Iconic Species to its Native Habitat: Cambodia was once part of the historic range of the Indochinese tiger, and reintroducing tigers would bring back a keystone species that has been missing for over a decade. Tigers play a crucial role in the ecosystem by maintaining balance. Their presence can help control herbivore numbers, benefiting the overall health of forests and other wildlife.

- Conservation Success Stories: Reintroducing tigers from India could offer a much-needed boost to Cambodia’s ecosystem and serve as a symbol of regional cooperation in wildlife conservation.

- Tourism and Economic Benefits: A successful tiger reintroduction could generate significant tourism revenue for Cambodia. Wildlife tourism is a growing industry, and the presence of tigers could attract nature enthusiasts, photographers, and conservationists from around the world. This could provide much-needed funds for further conservation efforts and support local communities, offering an economic incentive for protecting the newly reintroduced tiger population.

- Regional and Global Conservation Symbolism: If Cambodia succeeds in reintroducing tigers, it could become a model for other countries looking to restore lost species and reclaim wilderness areas for future generations. This could demonstrate that it is possible to bring back species that were once thought to be lost.

Indochinese tiger in Thailand – KLNP DNP / Freeland

Challenges, risks and considerations

- Subspecies Mismatch: One of the most debated aspects of this reintroduction is the fact that it involves a different subspecies. Cambodia was historically home to the Indochinese tiger, whereas the tigers being considered for reintroduction from India are Bengal tigers. While both subspecies share many characteristics, they have adapted to different ecosystems over time. Some conservationists argue that introducing a non-native subspecies could have unforeseen ecological consequences or dilute the genetic integrity of the local population, should any Indochinese tigers still exist. Others, however, point out that given the extinction of the Indochinese tiger in Cambodia, the introduction of a closely related subspecies might be the only way to restore tigers to the region.

- Habitat Suitability and Prey Availability: One of the key questions is whether Cambodia’s current landscape can support a viable tiger population. Much of Cambodia’s forest cover has been lost due to deforestation and land conversion, raising concerns about whether the country has enough suitable habitat to sustain tigers. Tigers require large, contiguous areas of forest with sufficient prey to thrive, and Cambodia’s prey populations – particularly deer and wild boar – have also declined dramatically. Without sufficient prey, tigers may struggle to survive or resort to preying on livestock, potentially leading to human-wildlife conflict. However, despite historical declines, concerted conservation efforts have led to the recovery of key prey species in Cardamom. Wildlife Alliance has invested years into protecting the habitat and rebuilding prey populations through anti-poaching patrols, replanting lost forest cover and prey restoration activities.

- Human-Wildlife Conflict: The potential for human-tiger conflict is a significant concern in any reintroduction project. Tigers are apex predators and, if reintroduced into areas close to human settlements, there is a risk of them attacking livestock or even people. Mitigating human-tiger conflict requires substantial investment in education, infrastructure, and compensation schemes for affected communities. Fortunately, the core zone of the Cardamom National Park is free from human settlements, with the nearest village 25 km away reducing the likelihood of direct human-tiger conflict. However, proactive mitigation and coexistence strategies are being actioned with plans for a Livestock Compensation Fund, ongoing community engagement/education programs and the development of community-based ecotourism.

- Poaching and Illegal Wildlife Trade: If you want to reintroduce any animal, you have to first solve the problem that caused their extinction. Cambodia’s history of illegal wildlife trade and poaching was one of the major causes of tiger expatriation from Cambodia and it continues to pose a significant risk to a reintroduced tiger population. Conservation organisations and the Cambodian government are committed to anti-poaching efforts in the Cardomom region to combat this. Wildlife Alliance manages 11 ranger stations that carry out over 5,000 patrols covering around 140,000 km every year. This level of protection has ensured continuous rainforest cover and zero elephant poaching since 2006.

- Costs and Long-Term Commitment: Reintroducing tigers is an expensive and long-term endeavour. The costs include translocating the tigers, monitoring them, managing habitats, preventing poaching, and resolving human-wildlife conflicts. Sustained financial and political commitment are required to ensure the success of the program over the long term. While the initial reintroduction might capture global attention, the ongoing management and protection of the tiger population will require considerable resources for years to come.