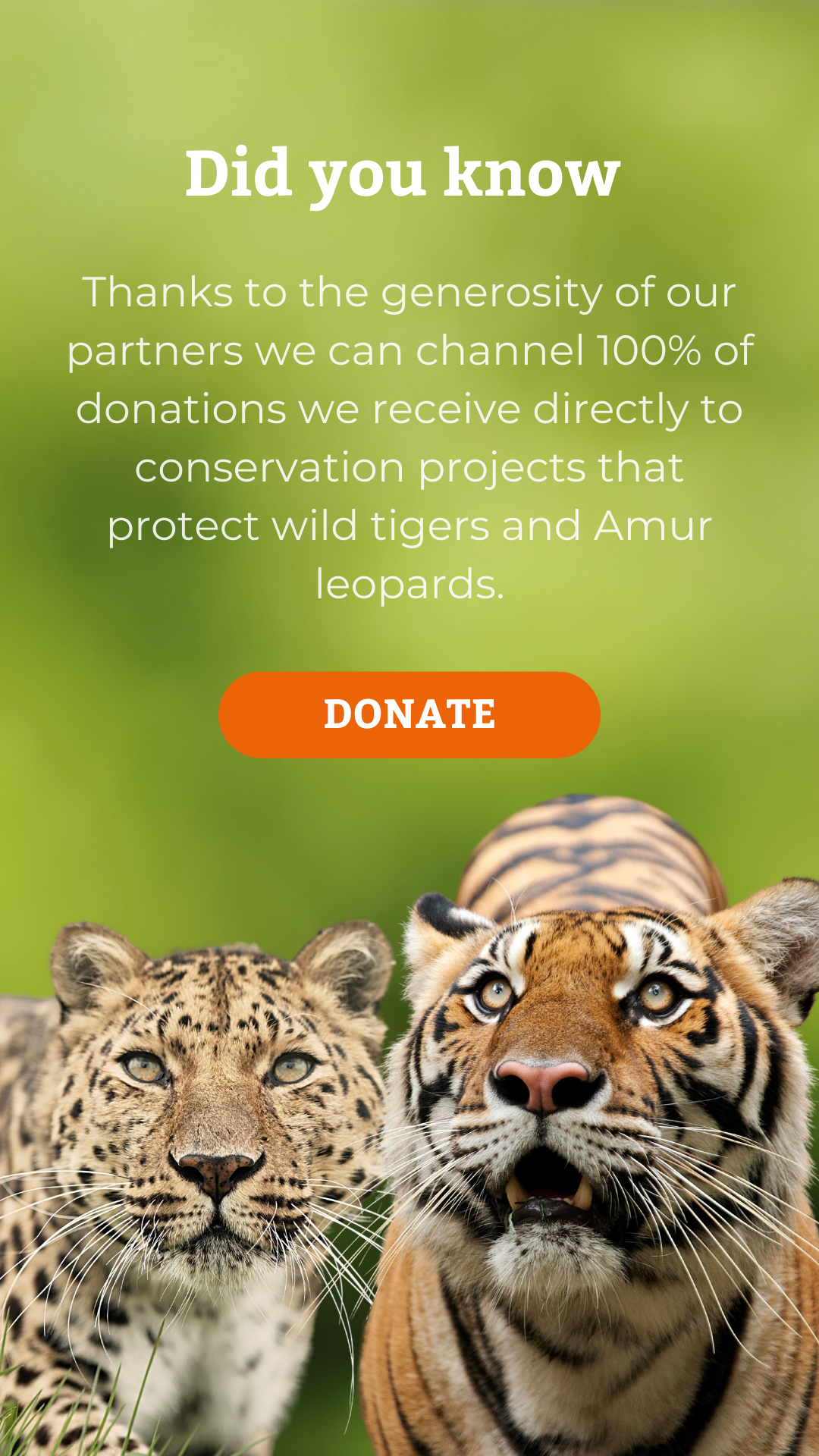

- Khao Laem National Park lies in the Western Forest Complex, connecting its upper and lower sections and hosting its own breeding tiger population.

- African Swine Fever is decimating wild boar, triggering declines in muntjak and a slight dip in gaur. Combined with poaching and illegal cattle grazing, these pressures underline the urgency for stronger ranger enforcement.

- Outreach, particularly with ethnic Karen communities, is key. It has opened dialogue, helping shift attitudes towards legal livelihoods and respect for park regulations.

In the heart of Thailand’s Khao Laem National Park, an ambitious project is underway to secure the Thai tiger population.

Since 2016 we have supported our implementing partner, Freeland Foundation, on a project in Thailand’s Khao Laem National Park (KLNP). Khao Laem is part of a contiguous series of 18 protected areas, known as the Western Forest Complex (WEFCOM), with a combined area of more than 20,000 km2.

Since the initiation of this project, conservation measures have significantly improved in KLNP by increasing the capacity of officials, who can now conduct thorough tiger population surveys, implement adaptive protection strategies, and mitigate human-tiger conflicts. Consequently, Khao Laem National Park is experiencing a recovery of tigers and certain prey species, validated by the continued presence of tigers over the last six years.

Prey in declining numbers

Until mid-2022, surveys documented an increase in key prey species, creating a conducive environment for tiger breeding and successful rearing of cubs. However, a newly released interim project report by the Freeland Foundation paints a mixed picture of tiger conservation in Thailand’s Khao Laem region. Although recent surveys confirm that tigers still roam this protected area, some prey species such as wild boar, muntjak and gaur have declined. This is likely due to African Swine Fever (ASF) which has swept through local wild boar populations, setting off a cascade of ecological impacts for tigers and other species. With fewer wild boar to hunt, tigers and other large carnivores may be turning their hunting focus to muntjak, creating added pressure on these smaller deer. Meanwhile, the already modest gaur population has also seen a slight dip, though tigers are thought to only occasionally prey on this colossal species due to its size.

Wild boar

This demonstrates that ongoing surveillance for new and emerging threats is essential to introduce effective mitigation measures promptly. Unfortunately, there is still no vaccine so there is little that can be done about the decline in Wild Boar from ASF once it is in the habitat. However, increasing protection for the remaining prey species against other threats will allow natural population recoveries. To guarantee success in park protection, officials need to improve the rates at which they intercept other threats like poachers of both tigers and their prey and illegal cattle grazing.

Freeland and DNP conducting ranger training in 2024.

Community outreach and engagement

However, effective enforcement alone is not enough. There must be equal investment in outreach and engagement with local communities. Many who live near the park—often ethnic Karen—have found themselves relying on activities that negatively impact wildlife, including poaching.

By forging positive relationships, the Freeland Foundation has seen glimmers of progress. Outreach efforts in these areas are conducted alongside law enforcement agencies, especially the Border Patrol Police (BPP), who are respected in these remote communities due to their rural development support, such as providing medical facilities and schools. From outreach conducted in 2023 and 2024, there is some traction being made with some hostile communities who are now more receptive to following park regulations and exploring legal vocations.

Community engagement work by the DNP and Freeland Foundation.