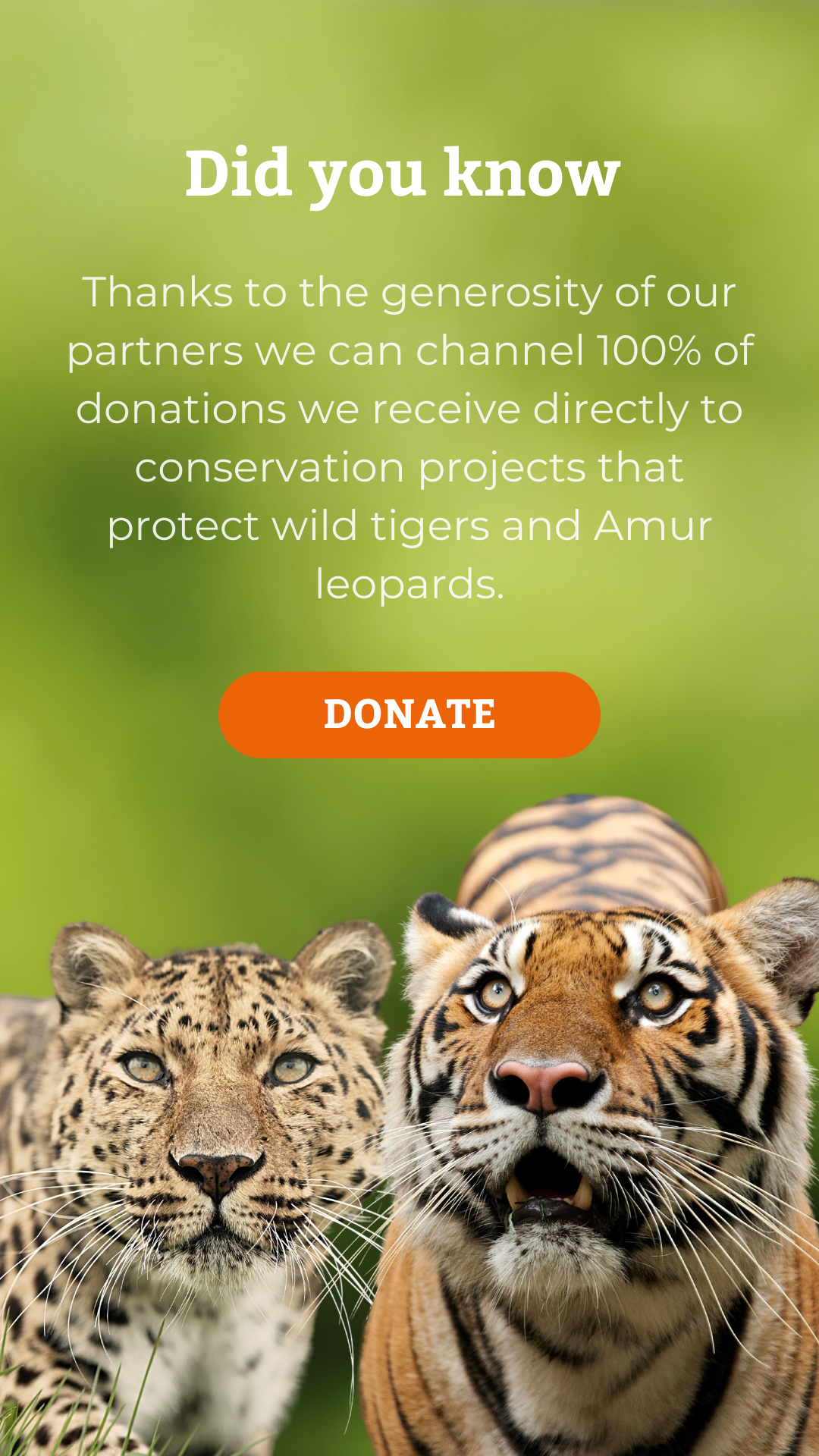

In a remote region of Russia’s Far East, something extraordinary is happening: the world’s rarest big cat is making a recovery.

In 2024, conservationists with the Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS) and Land of the Leopard National Park (LLNP), with longstanding support from WildCats Conservation Alliance, recorded the highest densities of Amur leopards ever recorded in Russia.

Researchers estimated a density of 1.86 leopards per 100 km², a 183% increase compared with the initial 2015 estimates of 0.65 leopards per 100 km².*

Camera trap data from 2024 reveals a landmark year for Amur leopard recovery

In early 2024, conservationists from WCS set up 130 hidden cameras across Land of the Leopard National Park in Russia’s Far East to check in on one of the world’s rarest big cats. The cameras were placed in 66 carefully chosen spots covering a vast 770 km² area. Over just 16 days, the team travelled more than 2,800 km, by car, quad bike, and on foot, to get the job done.

After three months, the cameras were collected and had captured over 9,000 images of wildlife, nearly 1,000 of them showing Amur leopards. From these images, the researchers were able to identify 28 individual leopards, up from just 16 recorded in 2015. Using this data, the team calculated a population density of 1.86 leopards per 100 km², the highest recorded in a decade of monitoring.

”“This is a landmark achievement... Our estimate of leopard population density serves as a new reference for what kind of recovery can be achieved for leopards in Northeast Asia.”

WCS Team

Camera trap image of an Amur leopard in LLNP during the population monitoring effort in early 2024. Credit – WCS & LLNP

What’s driving the Amur leopard’s comeback?

For over 20 years, WildCats Conservation Alliance has supported WCS’s work to protect Amur leopards in the Russian Far East. A key part of the recovery strategy has been to improve the quality of anti-poaching patrols. As law enforcement becomes more effective, poachers are deterred, and pressure on wildlife decreases. Prey animals, especially deer, are often the first to bounce back. In turn, leopards benefit from more food and safer conditions, leading to improved survival and steady population growth.

This recovery has been especially supported by the rising numbers of sika deer, the leopards’ main prey. In fact, sika deer are now at record levels in the study area, and their comeback is thought to be a major factor behind the increase in leopard numbers.

WCS has used this successful approach to recover tiger populations at other sites around the world, including Thailand’s Huai Kha Khaeng Wildlife Sanctuary, a success recently published in a scientific paper (Duangchantrasiri et al., 2024).

Camera trap image of Sika deer in LLNP in 2025. Credit – WCS & LLNP

Looking Ahead: Connectivity and Genetic Diversity

The comeback of Amur leopards in Land of the Leopard National Park is a powerful reminder that, with protection and enough prey, even the most endangered big cats can recover. But the work isn’t over. Looking to the future, conservationists are now focusing on two key challenges: keeping the population genetically healthy and making sure leopards can move between habitats.

There’s also growing interest in whether Amur leopards and their larger neighbour, the Amur tiger, start competing with each other now leopard densities are at an all time high in LLNP. Researchers will be watching closely to see how these two big cats interact.

*Source details:

Name: WCS Russia Leopard Final Report 2024

URL: https://conservewildcats.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/5/2025/05/WCS-Russia-Tiger-Final-Report-2024.pdf