When we talk about climate change, we often think first about people. Flooded homes, failed crops, and forced migration play centre stage. But climate change is also reshaping the lives of wildlife, including one of the most iconic and endangered species on Earth, the tiger.

Climate vulnerability across Asia

Asia is one of the regions most exposed to climate change because of its sheer environmental diversity. That means it’s exposed to almost every kind of climate threat: melting glaciers, intensifying monsoons and typhoons, rising sea levels, and worsening droughts.

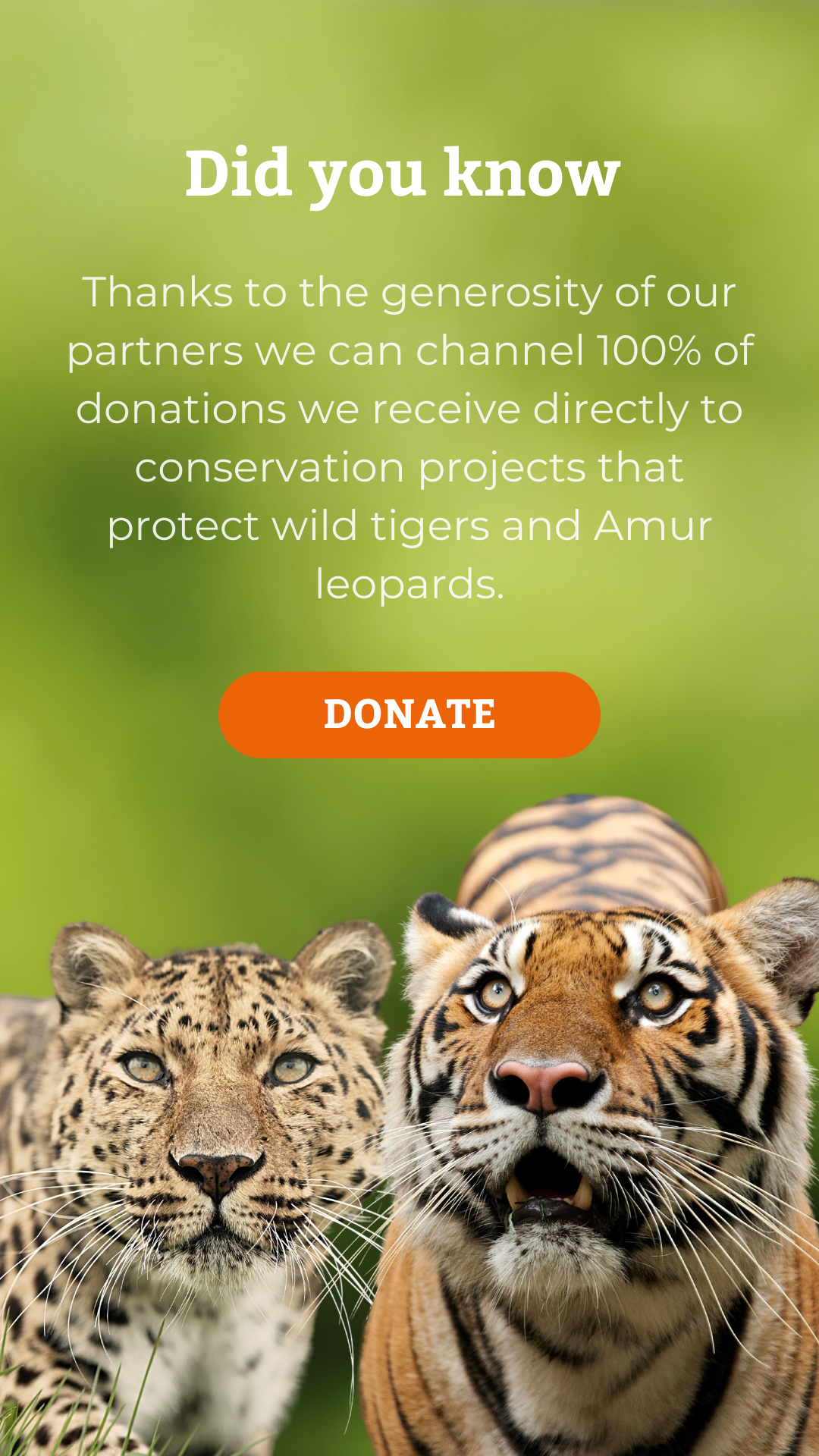

Tigers, which are endemic to Asia, are highly adaptable and able to live across Asia’s diverse habitats from mangrove swamps and tropical rainforests to dry grasslands, rocky hills, and snowy mountains. But while this adaptability is remarkable and a trait which could make the species more resilient to global warming, it can only go so far when the very ecosystems they depend on are all being reshaped by a rapidly changing climate. There are also other compounding pressures. For big land mammals, like tigers and leopards, moving isn’t simple. Human development has fragmented landscapes, and the climate is shifting faster than evolution can keep up so adaptation is hard.

Nowhere is this challenge clearer than in the Sundarbans.

The Sundarbans: a vanishing refuge

Straddling India and Bangladesh, the Sundarbans is the world’s largest mangrove forest and one of the most climatically vulnerable places on Earth. This vast, shifting landscape of islands, mudflats and tidal rivers is home to a unique population of Bengal tigers — the only tigers adapted to living in saline, mangrove-dominated ecosystems.

Mangroves are extraordinary natural defences. Their tangled roots absorb storm surges, reduce erosion, store carbon and protect millions of people along low-lying coasts. But climate change is pushing this system towards collapse.

Sea levels in the Bay of Bengal are rising faster than the global average. Warmer oceans are fuelling stronger cyclones that tear through forests, erode coastlines and push saltwater deep inland. Erratic rainfall means salt is no longer flushed from soils, young mangrove seedlings drown or fail, and the forest structure begins to unravel.

For tigers, this means shrinking habitat, declining prey and increasing stress.

Bengal Tigress, Panthera tigris, Sundarbans NP, India. Liz Leyden from Getty Images Signature.

What the science tells us

In 2019, Dr Sharif Mukul and colleagues published the first study to model the future of Sundarbans tiger habitat by combining sea-level rise and temperature change. The results were stark.

Under the worst-case scenario, no suitable tiger habitat may remain in the Bangladesh Sundarbans by 2070.

Crucially, the study did not even account for additional pressures such as rising salinity, invasive species, altered sediment flows, unplanned tourism, or nearby coal-fired power plants, all of which further degrade habitat quality. Taken together, the outlook may be even more severe than the models suggest.

Dr Sharif Mukul

Why saving tiger habitat is a global responsibility

The Sundarbans are not only vital for tigers, but they are also one of the world’s most important nature-based climate solutions. These forests sequester vast amounts of carbon while protecting coastlines from storms and erosion.

Recognising and financing these ecosystem services could help secure the future of both tigers and people. That means stronger global emissions reductions, increased climate and conservation finance, and international responsibility-sharing, especially from high-emitting countries that have contributed most to the crisis.

Tigers did not create climate change. Yet they may be forced to flee because of it.