Spanning the border between India and Bangladesh, the Sundarbans is the world’s largest mangrove forest and home to a unique population of Bengal tigers. This vast delta of rivers, islands and tidal creeks is also one of the regions most exposed to climate change. In our previous blog, we explored how rising seas, increasing salinity and intensifying storms are reshaping this fragile ecosystem and threatening tiger habitat.

This blog focuses on the people who live alongside tigers in the Sundarbans, and how climate change is altering their daily lives. It draws on research shared in our podcast by Amrita DasGupta, whose work examines the intersections between climate change, migration and gender in the Indian Ocean deltas.

Climate change and rising human–tiger conflict

Climate change is reshaping the Sundarbans in ways that directly influence encounters between people and tigers. Rising salinity affects mangrove growth, reducing forest cover and weakening the ecosystem’s ability to buffer storms. As forests thin and prey becomes harder to find, tigers are more likely to range beyond their usual territories.

At the same time, salinised soils and repeated flooding undermine agriculture, forcing people to rely more heavily on forest-based livelihoods such as fishing, crab collection and honey gathering. These activities increase the time people spend in tiger habitat, raising the likelihood of dangerous encounters. Climate change does not create human-tiger conflict in isolation, but it intensifies existing vulnerabilities and pressures, bringing people and tigers into closer proximity.

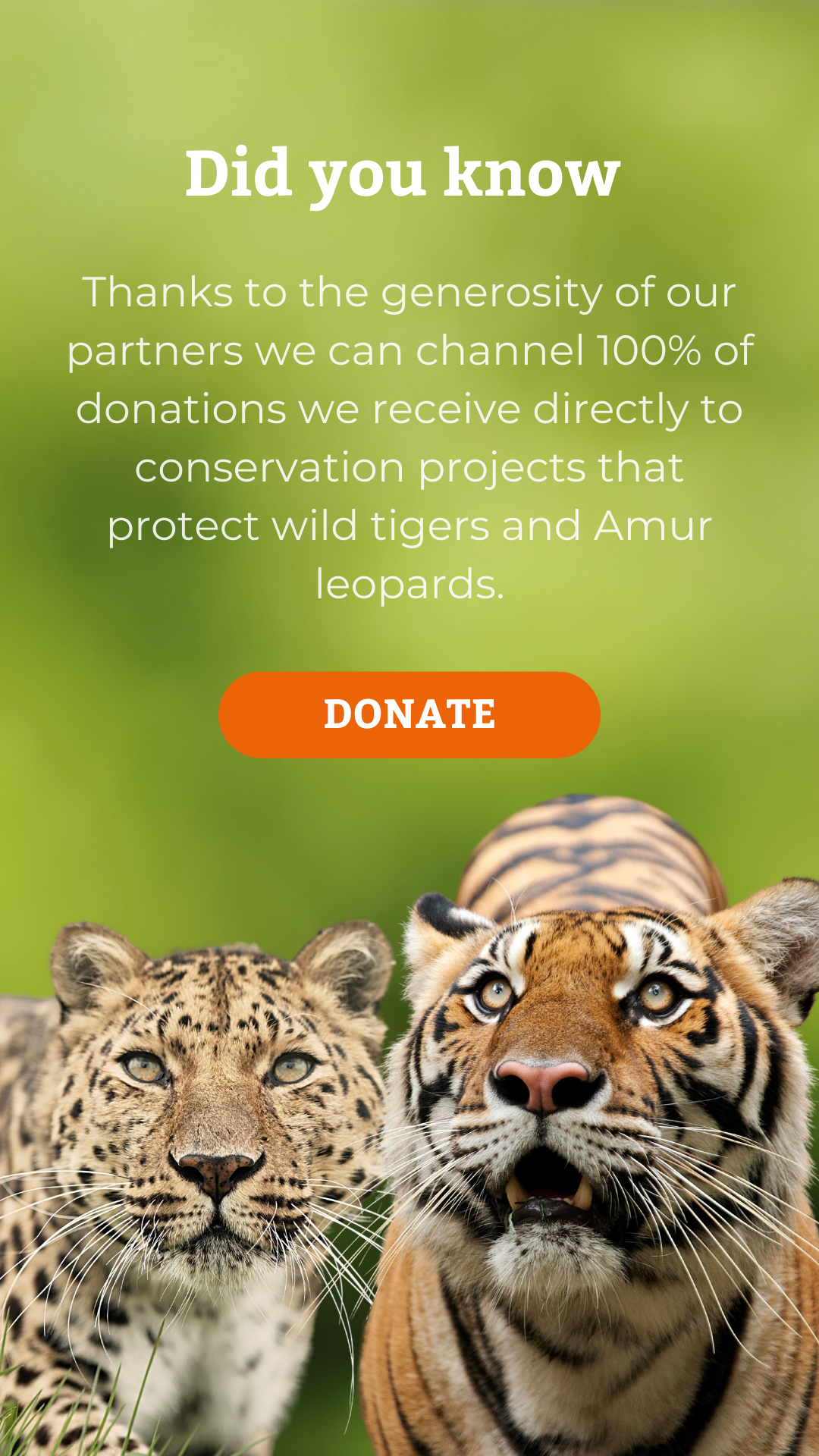

Sundarbans national park in Bangladesh by nicolasdecorte

Belief, blame and survival

Tigers hold a powerful place in local Sundarban belief systems, particularly through the guardian spirit of the forest, Bonbibi. The Bonbibir Johuranama, the principal folk text associated with the Sundarbans, distinguishes between taking from the forest out of need rather than greed. While this can encourage restraint with resource extraction, it has also shaped how blame is assigned after attacks.

When a tiger attack occurs, women whose husbands are killed may be accused of failing to observe rituals correctly and bringing misfortune upon their families. Widows can be labelled as cursed and excluded from community life and livelihoods tied to the river and forest. Many become dependent on relatives, NGOs or their children, while others face abandonment, loss of custody of their children or pressure to migrate. With limited land, little formal employment and weak social protection, exclusion quickly translates into extreme economic insecurity.

Amrita highlights how this loss of livelihood creates a direct pathway to exploitation. Women who cannot work locally may be forced to migrate in search of income, often without safe networks or legal protections. Traffickers exploit this vulnerability, offering work that leads instead to coercive labour or the sex trade in nearby cities.

These pathways are rarely addressed in conservation or climate policy, yet they are inextricably linked to the reality of human–tiger conflict in the Sundarbans.

Towards just solutions

As Amrita emphasises, reducing conflict requires more than awareness or cultural explanations, solutions must be practical and structural. She argues that belief systems persist because material alternatives are missing, so solutions must address that gap. She emphasises that people continue to enter the forest, and harmful interpretations of religion persist, because material alternatives are lacking.

Strengthening social protection, securing livelihoods and improving access to food, healthcare, and compensation would reduce dangerous dependence on forest resources and the risks that follow. For women in particular, she stresses the importance of dignified, local livelihood options that do not rely on forest access or expose them to exploitation, noting that exclusion from work is a key factor driving unsafe migration and trafficking, especially after cyclones and floods.