by Dale Miquelle PhD

When we establish a monitoring program to determine population trends for an endangered species, we often think of it as a necessary early warning system for when things go wrong. To be able to respond quickly enough and with confidence when a population is in decline, it is important to have a scientifically credible and reliable system to convince politicians, wildlife managers, and the public of the need for action.

That was largely our thinking when, in 2002, we started putting out camera traps in Southwest Primorskii Krai in Russia. We knew that the last Amur leopards occurred only here, and based on snow-track survey methods, it was estimated that there were only 20-30 individuals remaining of this northern-most sub-species of leopard, strung along the Sino-Russian border just above North Korea. There were a few regional wildlife refuges that had been created in this area, partially to protect leopards, but protection efforts were minimal, and support from the government was largely lacking. We knew that counting tracks in the snow, and trying to convert that into numbers of individuals was an exercise fraught with problems, and therefore not a reliable nor accurate way of estimating the abundance of this most highly endangered population of big cats. But we didn’t know if camera traps were the answer either. At that time, camera traps were still using film, limiting the number of pictures possible (usually to 36 images), which meant, along with short battery lifespans, that cameras had to be tended to every one to two weeks. This limited the number of cameras we could manage, and the amount of area we could survey. As digital cameras became available, lithium batteries developed, and camera prices fell, the potential to cover large areas became feasible. During this same period, we had learned how and where to set cameras to capture leopards and tigers on a regular basis. But only in 2014 was a survey deployed that covered nearly the entirety of Amur leopard range.

As we evolved this monitoring system, there were other important advances. With intense lobbying from local NGOs, led mainly by Dr. Yuri Darman of WWF, Land of the Leopard National Park was created in 2012, engulfing the smaller regional refuges and protecting 2800 km2 of key leopard habitat. WCS introduced SMART into the park – a system of monitoring and improving law enforcement efforts. About this same time, Sergei Ivanov, a key figure in the Putin-led Kremlin, was captivated by a video about Amur leopards produced by Vasily Solkin, a local filmmaker and conservationist. Ivanov vowed to help the leopard, and created a NGO intended to funnel money into its conservation. Management of the park was closely controlled, and poaching was not tolerated. Our monitoring systems – both SMART and camera trapping – were already in place and able to capture the changes occurring in this system. Anti-poaching efforts increased – more kilometers were traveled by patrol teams, both on foot and by vehicle. More citations were being issued, and more firearms were being confiscated. Poaching rates declined.

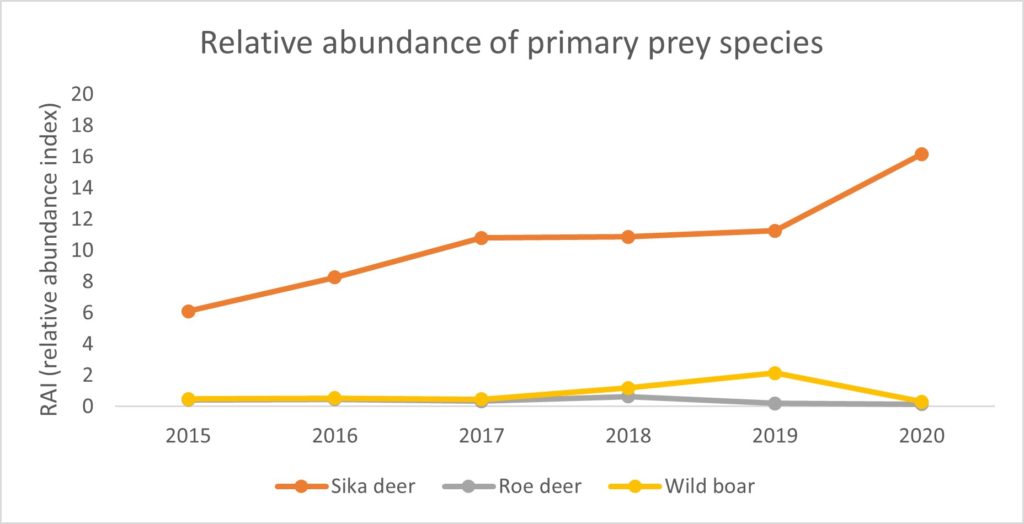

How the wildlife populations have responded has been truly inspiring. Since camera trap monitoring began across the entirety of the park the sika deer population has increased dramatically (see Figure 1). The fact that roe deer numbers have not also increased is not surprising, as sika deer, with their more catholic diets and willingness to eat most anything, tend to outcompete roe deer where they co-exist.

Figure 1. RAI of the three main prey species of tigers and leopards in Southwest Primorye

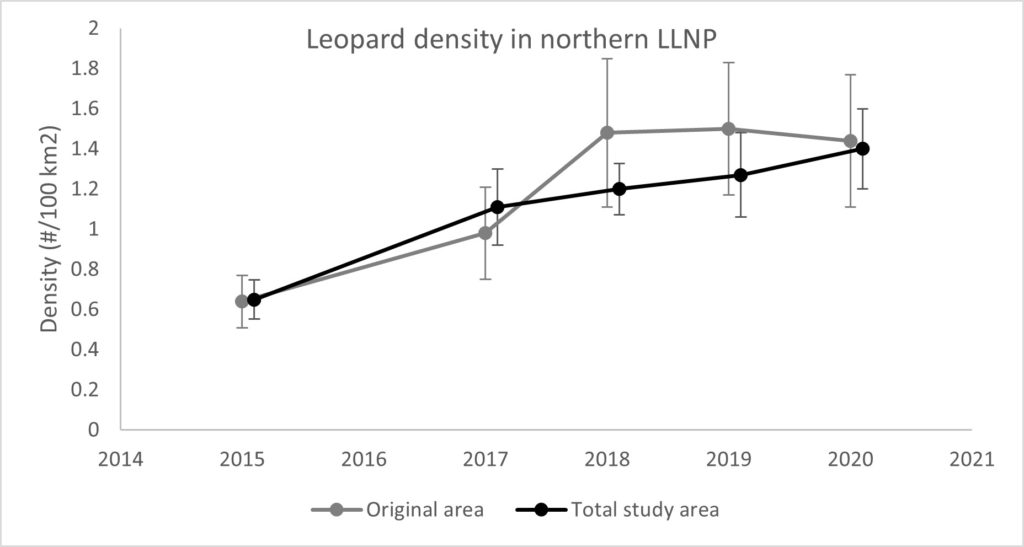

With the absence of poaching and increase in prey abundance, a dramatic increase in leopard density and numbers has occurred. In our long-term study area and in a larger area we have surveyed since 2014, leopard densities have increased significantly (Figure 2). Total numbers of Amur leopards counted in the park during a 90-day camera trap survey period have increased from 53 in 2014 to 86 in 2019 (with a peak of 98 in 2018). And not only have leopard numbers increased, but the endangered Amur tiger population has also greatly increased during this same period as well.

Figure 2. Density (individuals/100 km2) of Amur leopards in northern Land of the Leopard National Park, 2014-2020, showed a significant increase over time.

The other exciting spin-off of this recovery of big cats in Southwest Primorye is its impact on big cat recovery in nearby China. Young individuals of both leopards and tigers, finding little space for themselves in the increasingly crowded landscape of Southwest Primorye, are heading west, across the international border into China. There, authorities created the largest protected area for tigers and leopards in all of Asia, some 15,000 km2, to receive these Russian feline immigrants.

Security check permissions LLNP © WCS

This success is a demonstration that recovery of big cats is possible when strong anti-poaching efforts are enacted. It is also a tribute to the governments of both Russia and China, who have made major commitments to the recovery of these amazing cats. And it is a tribute to the heroes who stood up to protect these cats: Yuri Darman, who led the charge to create Land of the Leopard National Park, Vasily Solkin, who so poignantly portrayed their plight in film and in print, and Sergei Ivanov, who committed the Russian government to this task of recovery.

Our monitoring programs are often designed to warn us of oncoming catastrophes, but when everything goes right, they also demonstrate what success looks like. The battle is not over – the Amur leopard population is still too small, expansion of its range is still a priority, and continued vigilance is essential. But let’s take a moment to revel in this victory and enjoy what are our camera traps are telling us – Amur leopards are back!

Dr Dale Miquelle is WCS Country Director of WCS Russia and a world authority on Amur leopards and Amur tigers. He has lived in the Russian Far East dedicating his life to wildlife conservation since 1992.