- The Sikhote-Alin mountain range houses three protected areas, with the Sikhote-Alin Biosphere Reserve being the largest, covering 4% of Amur tiger habitat. The region has limited infrastructure and a sparse population, with the town of Terney serving as a hub for conservation efforts.

- Despite the region’s remoteness and challenging environment, people coexist with Amur tigers and depend on the forest for their livelihoods. Communities engage in activities like hunting, fishing, logging, and agriculture.

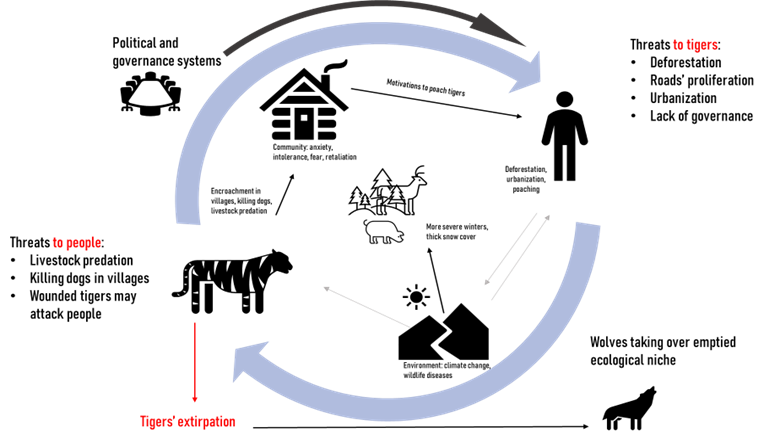

- Habitat loss and fluctuations in prey populations have led to interactions between humans and tigers, occasionally resulting in conflicts. Attitudes toward tigers among local communities vary, with some expressing negative views due to perceived threats, while others support tiger conservation efforts. Research, like Anna Klevtcova’s work, is essential to better understand and address these dynamics.

The location

Map of Amur tiger habitat and 5 northernmost settlements of Primorye krai and Vladivostok city (Hebblewhite et al. 2014).

The Sikhote-Alin mountain range, situated in the Russian Far East, stretches along the Sea of Japan and shares a border with China and North Korea.

The mountains contain some of the most diverse and intact temperate mixed and broadleaf forests and are renowned for extraordinarily high numbers of plants and invertebrates, many of which cannot be found anywhere else in the world. The Amur Tiger, often referred to as the Siberian Tiger, stands as the world’s largest big cat and a magnificent representation of the region’s wildlife. Within the Sikhote-Alin Mountains lies nearly the entire surviving population of this culturally revered and endangered tiger subspecies.

The Sikhote-Alin mountain range contains three protected areas (PAs). The largest of these PAs, the Sikhote-Alin Biosphere Reserve, accounts for 4% of the Amur tigers remaining habitat and is neatly situated between the mountain crest and the sea.

The Primorye region, home to the Sikhote-Alin Reserve, is populated disproportionately with the majority of people residing in the urban south areas and a very sparse low population in the northern districts. Close to the reserve, the small town of Terney functions as an administrative, logistical, and transportation hub for the Primorye region, connecting rural villages in the north with larger and more developed towns including Vladivostok in the south. Terney also plays a role as a major conservation hub, significantly contributing to Amur tiger scientific research, conservation, and education.

The people

While this region is remote, the weather unforgiving and the landscape rugged, there are still people who call it home. The livelihoods and culture of these communities continue to be closely linked with the forest landscape.

Adjacent to the Sikhote-Alin Biosphere Reserve are state forestry lands used for commercial logging, hunting, fishing, collection of non-timber forest products, and small commercial agricultural activities by locals (Goodrich et al. 2010). The majority of people in adjacent villages are hunters and fishers, using these activities for both subsistence and as a commercial activity. Plastun is the most populated town in this region comprised of 4,791 people followed by Terney with 3,139 (Federal State Statistics Service, 2020).

Historically, north of the Sikhote-Alin Biosphere Reserve was inhabited by the Udege, Nanai, and Orochi peoples who currently reside in Agzu and other northern villages of the Khabarovsk and Primorye regions. Human population numbers dramatically plummeted in the northernmost villages – Amgu (695), Malaya Kema (478), and Agzu (149) (Federal State Statistics Service, 2020).

Human-tiger interactions

Tourists walking on the beach alongside Udobnaya Bay in Sikhote-Alin Biosphere Reserve sprinkled with Amur tigers paw prints. Photo: Anna Klevtcova

Historically, the Amur tiger range exceeded 400,00 sq. km but with extensive hunting, logging, urbanization, and road proliferation it was reduced by almost four times over decades. Extensive habitat loss and fluctuations in prey population increase the likelihood of interactions between people and tigers, at times leading to a conflict.

Despite their charisma, coexistence with large carnivores like tigers can be challenging and always requires a certain degree of tolerance from local communities.

A recent study revealed that residents of small remote villages participating in hunting, fishing, logging, and forest resource extraction in Amur tiger habitats (Goodrich et al. 2010, Mukhacheva et. al 2015) expressed a very strong negative attitude toward tigers. They accused the species of predation on livestock, competing for game, killing dogs, and threatening people’s lives (Skidmore 2023). However, another study conducted by Mukhacheva et al. (2022), instead uncovered strong support for tiger conservation from rural communities.

It is therefore clear that much more research is needed for conservationists to understand the human-tiger dynamic in this region and understand what stands behind people’s attitudes and behaviours. Someone currently researching the social, natural, and spatial factors in this region to understand and address Amur tiger poaching is Anna Klevtcova. Anna, who is embarking on a PhD in Interdisciplinary Ecology at the University of Florida, is the first recipient of the WildCats Conservation Alliance Professional Development Award*.

You can find out more about Anna here.

*This Professional Development Award aims to develop skills and knowledge within projects receiving funds from WildCats Conservation Alliance. The work undertaken, whether academic or practical must be of benefit to both the project where they work and their own personal career. The applicants are carefully chosen by a panel of experts.