- Indigenous Primorye people share a historic bond with tigers evident in material culture and folklore. Carvings from II-I millennium B.C. in Khabarovsk depict this enduring connection, especially among Udegei, Orochis, Nanais, Negidal, and Ulchi people.

- Tigers are revered as sacred defenders and guardians, integral to kinship in indigenous beliefs. Killing tigers is strictly prohibited; folklore emphasizes rituals, and stealing prey or disrespecting paw prints is forbidden.

- Amid cultural shifts, questions arise about the persistence of indigenous beliefs and their impact on conservation. Census data (2020) highlights the distribution of indigenous groups, prompting consideration of evolving tiger roles and conservation implications.

The people

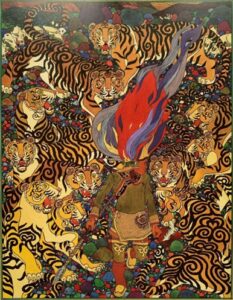

“Tiger”, Gennadii Pavlishyn. Print: Rech, 2012

For thousands of years, the indigenous communities of Primorye and Priamurye have coexisted with tigers, as evidenced by their material culture, stories, and beliefs. Carvings of tigers on rocks along the Kiya and Amur rivers in the Khabarovsk region and Prymorie trace back to the II-I millennium B.C. Among these indigenous groups, including Udegei, Orochis, Nanais, Negidal, and Ulchis, tigers have held a sacred and central space in their cultures since ancient times.

Presently, Udegei and Orochis people inhabit neighboring regions of the Sikhote-Alin mountain range, while Nanais reside along the Amur shores in the Khabarovsk region. Negidal communities are situated in the lower stream of the Amgun, and Ulchis live in the Ulchskii district of Khabarovsk. As per the 2020 population census, Nanais are the most numerous among these five groups, totalling 11,109 people. Ulchi people follow with a population of 2,390, Udegei with 1,261, Negidal with 467, and the smallest group being the Orochi, with only 392 individuals identifying as Oroche.

Tracks2021©WCSRussia

Folklore

The foundational culture of indigenous groups centers around a profound belief in the genetic connections between humans and animals, with a particular emphasis on tigers and bears. Folklore of Orochis, Nanais, Udegei, and Negidal includes narratives of marriages between humans and tigers, depicting their descendants as the initiators of kinship. In such tales, tigers are perceived as defenders and guardians, bringing hunting luck and warding off evil spirits.

This belief system shapes and directs the overall relationship between people and tigers. The killing of a tiger was strictly forbidden, with Orochis believing that a hunter who slays a tiger would face retaliation from another tiger. Accidental tiger killings required offerings and specific burial rituals. Stealing a tiger’s prey was also strictly prohibited, though Orochis believes tigers intentionally left prey as an act of care. Additionally, stepping on tiger paw prints was forbidden, and in such cases, a Udegei hunter, for instance, would measure seven steps away, kneel, and pray for the tiger to send him game.

Curiously, folklore among Orochis, Nanais, Negidal, and Ulchis frequently depicts instances of people assisting tigers. Narratives include tales of hunters raising tiger cubs and hunting together, as well as scenarios where tigers seek help from humans, bringing hunting luck to their saviors.

While unquestionably revered, indigenous folklore portrays the tiger with a dual nature. Tigers can serve as a benevolent spirit, known as ‘Kuty Mafa,’ guiding people, or as a malevolent force, termed ‘Amba’ in Udegei language, causing harm. Udegei belief holds that a threatening tiger signifies a loss of control, suggesting the tiger has gone “crazy” and severed ties with its supposed ‘owner,’ controlled by the mountain spirit Dussy. Exceptions to this rule are linked exclusively to instances of blood revenge in their mythology.

Contemporary human-tiger relationships

The spiritual culture of Far Eastern indigenous minority groups has undergone extensive study, particularly concerning the role of the tiger as both a totem and a spirit. However, in our rapidly changing world marked by cultural assimilation, geographic mobility, and technological advancements, it remains crucial to assess the current status of these beliefs. How many individuals still adhere to these cultural tenets? What role does the tiger play in modern indigenous cultures? Are traditional respects for the ‘ancestor’ being maintained, or are there shifts toward extractive practices driven by market demands? Additionally, understanding whether indigenous communities contribute to tiger poaching is essential. Asking these questions is vital for informing conservation strategies and the development of preventive measures against wildlife crimes.

This blog was written by Anna Klevtcova, the first recipient of the WildCats Professional Development Award as a legacy of the WildCats 2022 Year of the Tiger campaign. You can find out more about Anna’s research here.

This blog was written by Anna Klevtcova, the first recipient of the WildCats Professional Development Award as a legacy of the WildCats 2022 Year of the Tiger campaign. You can find out more about Anna’s research here.

References

1. Подмаскин, В. В. (2020). Древние представления о тигре и леопарде у коренных народов Нижнего Амура и Сахалина как историко-этнографический источник. Манускрипт, 13(12), 120-126.

2. Тигр. Геннадий Павлишин. Изд-во: Речь 2012.

3. Этнос и природная среда. Ред.: Тураев В.А. Владивосток: Дальнаука, 1997. 153 с.

4. Старцев, А. Ф. (1996). Материальная культура удэгейцев (вторая половина XIX-XX в.). ДВО РАН.

5. Подмаскин, В. В. (1991). Духовная культура удэгейцев XIX-XX вв.