Defying the odds, new Perhilitan-Panthera study shows an effective approach to counter poaching of the Malayan tiger.

- A study from Malaysia’s Department of Wildlife and Panthera shows that despite a surge in poaching of the critically endangered Malayan tiger, deep forest patrol teams, such as PERHILITAN’s elite counter-poaching unit ‘SPARTA,’ have reduced poaching incursions by up to 40% in Southeast Asia, offering hope for the subspecies.

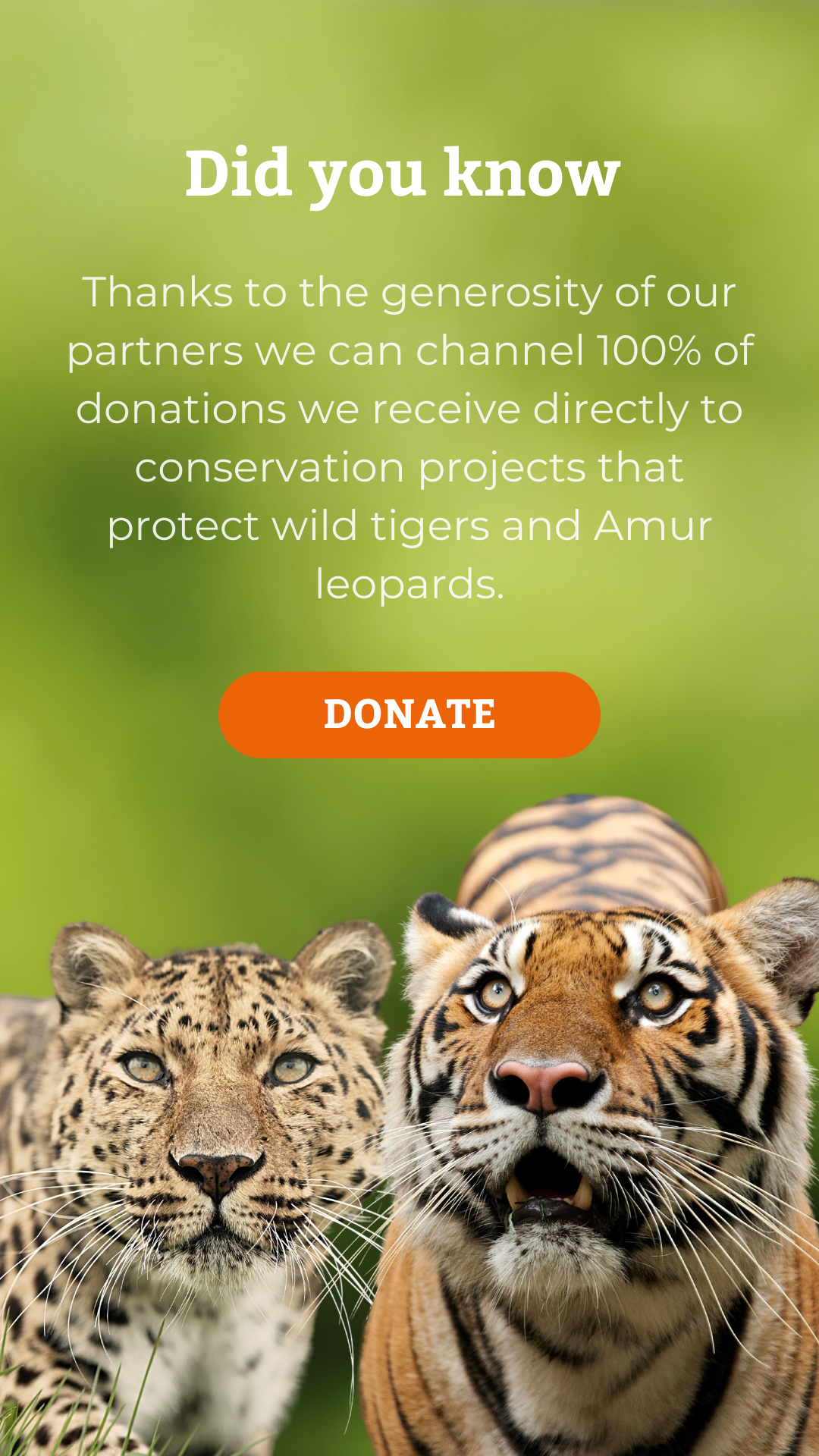

- The Malayan tiger, the most endangered tiger subspecies with fewer than 150 individuals in Peninsular Malaysia, faces challenges due to the demand for tiger body parts. Conservation efforts include increased ranger numbers, training, and initiatives like Operasi Bersepadu Khazanah.

- The success of the deep-forest counter-poaching strategy relies on a combination of traditional skills and modern techniques, focusing on intercepting poaching teams and adapting tactics through rigorous learning and debriefing processes. It is essential to address poaching prevention within poachers’ communities to complement protection efforts.

Despite a surge in poaching over the last decade, advances in counter-poaching operations have made poaching incursions less deadly, according to a new study from Malaysia’s Department of Wildlife and National Parks (PERHILITAN) and Panthera, the global wild cat conservation organization. In a sign of hope for the Critically Endangered subspecies, the study shows how effective deep forest patrol teams can be in protecting tigers.

The Malayan tiger is the most endangered of the six tiger subspecies. With under 150 estimated to occur in Peninsular Malaysia, last year Malaysia’s Department of Wildlife and National Parks (PERHILITAN) declared the subspecies could become extinct within five years. Recovering the Malayan tiger is made challenging due to the sustained market for tiger body parts, and where protected areas are large mountainous tropical forests guarded by small teams of rangers.

Published in Frontiers in Conservation Science, the rigorous new study examines an eight-year project protecting tigers in Kenyir, Taman Negara, using a method developed for evaluating police work in reducing urban crime. This study provides evidence that tactics developed by PERHILITAN’s elite counter-poaching unit ‘SPARTA’, in conjunction with Panthera’s civilian scout teams, reduced the success of Vietnamese, Thai and Cambodian poaching incursions by up to 40% in the midst of a Southeast Asian snare crisis.

In the last five years the Malaysian government has launched a number of initiatives to protect the Malayan tiger and prevent further poaching including Operasi Bersepadu Khazanah (OBK) and the Veteran-Orang Asli Community Rangers under the Biodiversity Protection and Patrolling Program (BP3). Protection also includes Terengganu State Government’s gazettement of the 30,000ha Kenyir State Park in 2018, and Pahang’s recent gazettement of the Al-Sultan Abdullah Royal Tiger Reserve, ensuring more intact forests for tiger recovery. Under these initiatives, and support from NGO scout teams, ranger numbers have risen in Malaysia. But while a good start, it is ranger quality, not only quantity that counts, says lead author, Panthera Malaysia Country Manager, Lam Wai Yee.

“Our forests need guardians, but if teams lack the direction, resources and training, they run the risk of being ineffective in controlling poaching. With the deep-forest counter-poaching strategy, we concentrated on investing a higher level of training on a smaller team.”

Lam explained that much of the success was due to fusing traditional skills with cutting-edge techniques.

“A real game changer in the last five years, has been the recognition that indigenous Orang Asli people have forest skills that enable them to be very effective forest guardians. When you marry those skills in tracking and bushcraft with a dedicated analyst who can predict poachers’ movement patterns, you have a very effective team.”

With evidence suggesting the common tactic of systematic snare removal on its own has little impact on reducing the problem, the joint PERHILITAN-Panthera team recognised early on that new approaches were needed.

Co-author and counter-poaching instructor Zainal Abidin Mat added, “Our strategy differs in that our focus is first and foremost on finding and intercepting the poaching team. Only after concluding the arrest the team would begin sweeping for snares. Through trial and error we’ve learned that if we begin removing snares too early, the poachers move, and will continue to make incursions.”

A key part of the strategy was developing a rigorous system of learning and adapting at the site. Lam explained that it is easy to identify mistakes, but harder to actually learn lessons and improve.

To get better at this, the analyst together with rangers began conducting detailed debriefings after every single operation, to identify why it failed, and how we could do things differently next time. New tactics would then be tested in role-playing scenarios, before our instructors built immersive and highly realistic training modules.

Co-author and Panthera Problem Analyst Phung Chee Chean added, “We all had to be frank and open about why something didn’t work, and develop a solution together. It was important above all that the rangers themselves were all on-board with the new tactic and understood why we were doing it that way.”

Co-author and Panthera Counter-Wildlife Crime Research and Analytics Lead, Dr. Rob Pickles, commented, “Good evaluation in conservation is extremely rare, which may lead to the repetition of ineffective approaches, wasting precious time and money. We played devil’s advocate in this study. We weren’t content to see a problem decline and claim credit, we tested ourselves to prove that the deep-forest counter-poaching strategy caused the specific Vietnamese, Thai and Cambodian poaching problems to decrease, and not other factors. Going through this process was tough, but gave us a more honest understanding of how effective the strategy was.”

Co-author Dr. Gopalasamy Reuben Clements, who is now based at ZSL and Nature Based Solutions cautioned, “While the study shows the strategy did prevent tiger poaching, it also highlighted limitations. Even though the rangers had significantly increased the risk of arrest to poachers entering Kenyir, we found this did not deter Vietnamese poachers from continuing to attempt to poach.”

The authors emphasise the need to combine the tiger protection work with initiatives focused on prevention of poaching within the poachers’ communities. The study identified issues involving migrant worker exploitation and debt traps that encourage people to become poachers and could become targets of a prevention strategy.

Following the success of the deep-forest counter-poaching strategy, rangers across the peninsula are currently being trained in techniques, with the first cohort of instructors certified last year and a new protection team replicating this strategy is being implemented in the country’s new Al-Sultan Abdullah Royal Tiger Reserve.

PERHILITAN Director General Dato’ Abdul Kadir stated, “We are racing against time to save our iconic tiger, but our department is committed to conserving Malaysia’s wildlife for future generations, and strategies like deep forest counter poaching operations, which have shown evidence to work, provide us with powerful tools to do just that.”