- Tigers seen as pests and competitors: Hunters in the Far East view Amur tigers as pests and competitors, despite protective measures and penalties for killing them.

- Motivations beyond money: While financial gain motivates some hunters, others are driven by thrill-seeking and conflicts, posing challenges to conservation efforts.

- Disconnect in hunting management: Issues in Russia’s hunting management system, such as legislative inefficiencies and a ‘us vs. them’ mentality among hunters, hinder conservation efforts and disconnect hunters from decision-making processes.

This blog was written by Anna Klevtcova, the first recipient of the WildCats Professional Development Award.

On the way to the local airport to hop on the plane back to Terney from Vladivostok I’m talking to a taxi driver who seems desperately looking for a conversation to help him stay awake until lazy winter dawn finally breaks through a dark and cold Far Eastern night. “Oh, you work with tigers!” he exclaims as I answer his question about my job. “I have a friend who put down four mattresses* at once in the Khabarovsk region!”. I look at him with a mix of resentment and surprise. “Why would someone do that?” I ask. “Well, there are so many of them and they are pests, someone has got to take care of it.”

*‘Mattress’ is a slang term for tiger among local hunters (old Soviet Union mattresses had striped patterns

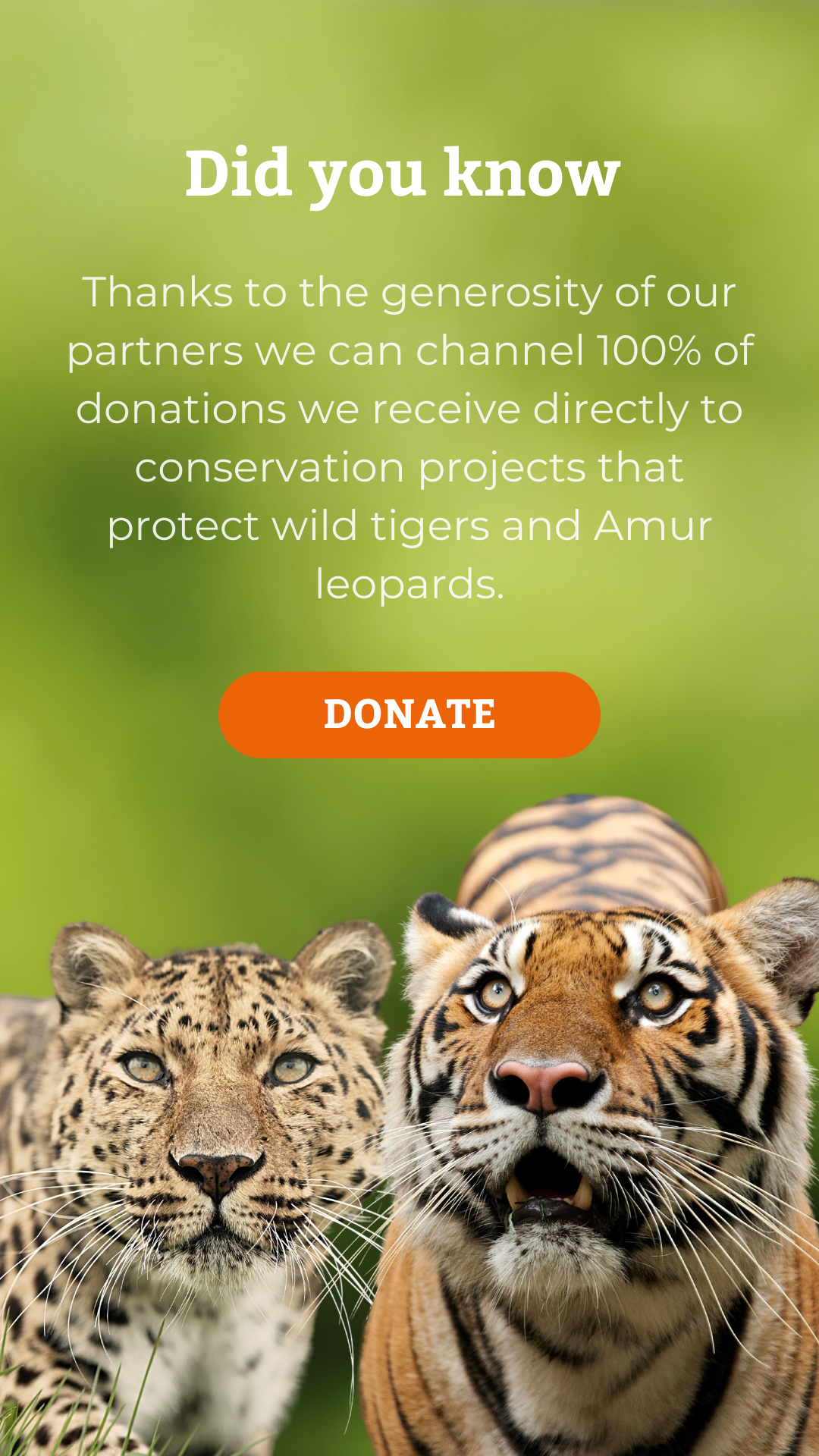

Amur tigers – pests, hazards and game competitors?

Although not well documented yet, the notion of tigers being pests, hazards, and game competitors seems to have a firm position in Far Eastern hunter’s minds. Despite rigorous protection measures, substantial financial penalties, and even criminal prosecution, alarming posts uncovering attempts to sell tiger parts keep popping up in local news channels.

“95% of hunters will pull the trigger when they see a tiger”

Roman Kozhichev, Former Deputy Director of the Terrestrial Protection Department at Sikhote-Alin Nature Reserve, Roman Kozhichev.

Money doesn’t always serve as the primary motivator for hunters. While just over half of hunters surveyed in recent ethnographic research cited financial gain as a reason for killing tigers, the remaining respondents identified thrill-seeking and conflicts as driving factors. These findings suggest a troubling reality, a significant portion of the hunting community may not be swayed by financial incentives, rendering crime prevention measures aimed at reducing profits from tiger parts ineffective for this subset. Essentially, even if illegal tiger trafficking for profit from Russia were completely eradicated, tigers would still face threats from other motives that are not yet fully understood or addressed.

Other motives for hunting

Several Russian researchers have highlighted various issues plaguing the current hunting management system in Russia. These include legislative inefficiencies, inadequate funding, lack of oversight, outdated game population monitoring methods, and a failure to protect biological resources. The prevailing conceptual approach effectively excludes hunters from game and resource management, fostering a divisive ‘us vs. them’ mentality among forest users that discourages involvement in the protection and conservation of natural resources (Matveichuk 2012, Vinober 2016, Danilkin 2017). Hunters are disconnected from the landscapes they inhabit and the decisions made in relation to these habitats.

Interestingly, findings from recent socio-anthropological research conducted in Primorye by HSE University indirectly supported concerns about people’s engagement in decision-making processes. Local residents express a feeling of detachment from natural resources, considering them as belonging to the government, state inspectors, and industries rather than themselves. Consequently, individuals often perceive their own activities such as fishing, logging, or hunting for personal needs as akin to theft. The influence of immediate family members of hunters who accept and support unlawful actions within the family environment, may also influence a hunter’s decision to pull the trigger.

Photo hunting

In 2020, we initiated a pilot study in Terney to assess the effectiveness of photo contests as a tool for social data collection and to gauge children’s attitudes towards tigers. Dubbed ‘Photo Hunting’, we proposed five tiger-related topics and made the contest open to families and school children from Terney and nearby settlements.

Among the various findings, one particularly intriguing observation emerged, in the photography category ‘People through tiger eyes’ individuals submitted photos depicting people as chunks of meat. Further studies are necessary to carefully decipher the implications of this current perception of tiger-human interactions to determine whether it might have potential negative effects on conservation efforts in the area.

Although many questions remain unanswered, the upcoming summer holds the promise of unveiling previously unexplored aspects of hunters’ contributions to the future of Amur tigers and the role of tigers in their belief systems. As we enter the new year, we look forward to a prosperous time filled with new opportunities, meaningful discoveries, and promising results.

This blog was written by Anna Klevtcova, the first recipient of the WildCats Professional Development Award as a legacy of the WildCats 2022 Year of the Tiger campaign. You can find out more about Anna’s research here.

This blog was written by Anna Klevtcova, the first recipient of the WildCats Professional Development Award as a legacy of the WildCats 2022 Year of the Tiger campaign. You can find out more about Anna’s research here.