On July 29th, marking Global Tiger Day, the Global Tiger Initiative introduced the latest iteration of the Global Tiger Recovery Program (GTRP 2.0) for the years 2022 to 2034.

- Global Tiger Recovery Program (GTRP) was launched in 2010 under the Global Tiger Initiative (GTI) by the World Bank to save wild tigers. Tiger Range Countries (TRCs) committed to doubling wild tiger populations by 2022.

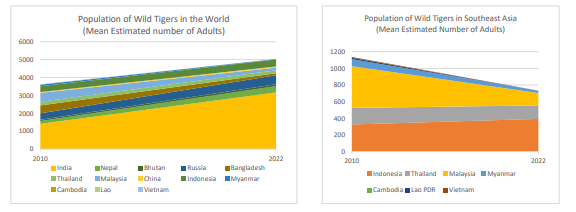

- Retrospective analysis shows mixed results: success in South Asia and Russia, alarming decline in South East Asia. Challenges include lack of tiger governance, habitat loss, human-wildlife conflict, and prey depletion.

- GTRP 2.0 aligns with the Post-2020 Global Biodiversity Framework, providing an opportunity for TRCs to integrate tiger conservation with global goals. Anticipated outcomes include cross-sectoral conservation, increased investment, habitat protection, conflict management, and reduced wildlife trade.

The original Global Tiger Recover Program (GTRP)

In 2008 the World Bank established the “Global Tiger Initiative” (GTI), an assembly of all the Tiger Range Countries (TRCs) and tiger conservation stakeholders with the aim of saving this iconic species from extinction in the wild. This initiative set out the first Global Tiger Recover Program (GTRP) in 2010 with the ambitious target of reversing the rapid decline of wild tigers across their range and doubling their population numbers by 2022. Alongside these top-level targets, the GTRP set out urgent thematic actions at a national level to strengthen wild tiger conservation in sync with this global goal.

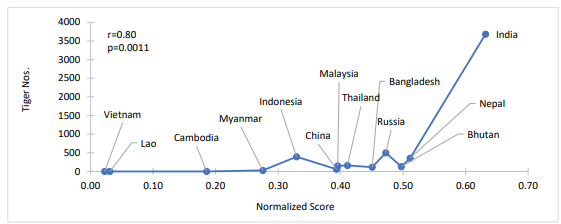

The first GTRP helped to pull focus to wild tiger conservation and secure a collective commitment from TRCs. The performance of TRCs in their efforts to implement the goals and objectives of the GTRP is assessed against a scoring system that is normalised to ensure fairness and comparability between them. The scoring system not only provides an assessment of current efforts but also offers a mechanism for feedback and improvement. It also allows stakeholders, including governments, conservation organizations, and the public, to monitor progress and hold TRCs accountable for their commitments. As you can see in below there is a strong correlation between scores and tiger numbers.

Fig 1. GTRP score vs tiger numbers

While new data released by the IUCN in 2022 suggested the first potential climb in tiger numbers in decades, the progress is uneven. Tigers remain threatened and there are still fewer than 5,000 left in the wild limited to just 10% of their historical range. Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Nepal, China, and Russia have made significant steps in growing and safeguarding their tiger populations. Key to their success is strong political will, institutionalising tiger governance, habitat protection, anti-poaching, prey augmentation organised field implementation, and proper resource allocation. However, in South East Asia (SEA), challenges persist. Widespread poaching, inadequate patrolling, proximity to wildlife trade hubs, habitat loss/fragmentation, and limited investment hinder progress.

Fig 2. Population status of tigers in the world and in Southeast Asia 2010 -2022

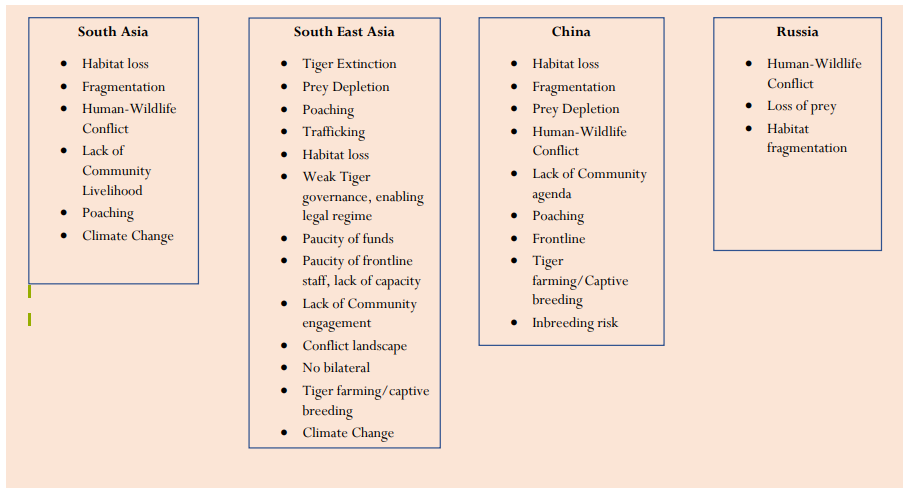

Figure 3 illustrates stressors affecting all TRCs and highlights additional issues in Southeast Asia. Therefore, during the Fourth Asia Ministerial Meeting on Tiger Conservation hosted by Malaysia in 2022, Southeast Asian TRCs collectively decided to prioritise common actions through the South East Asia Tiger Recovery Action Plan (STRAP). Each SEA TRC undertook further consultations to determine their priority STRAP actions which are detailed in the GTRP 2.0 document.

Fig 3. Limiting factors / stressors of GTRP performance

GTRP 2.0: Future focused

GTRP 2.0 aligns with the Post-2020 Global Biodiversity Framework, aiming to address the urgent biodiversity crisis. The GBF, endorsed by 188 countries including all TRCs, coincides with the early phase of the new Global Tiger Recovery Program (2023-2034). This presents a special chance for TRCs and institutions to harmonize tiger conservation with the global framework’s goals.

The following outcomes are anticipated from the implementation of the GTRP 2.0. A set of 56 KPIs have been agreed upon to measure progress toward these outcomes, these can be found in the full GTRP 2.0 document.

Overarching outcomes:

- Cross-sectoral approach in TRCs for tiger conservation with strong institutional support.

- Increased political and financial investment by TRC governments, support from funding agencies, and the private sector.

- High-level protection for tiger and prey populations at country and transboundary levels.

- Implementation of data-driven planning, monitoring, and habitat management for tigers, prey, and habitats.

- Effective management of human-wildlife conflict with stakeholder engagement.

- Recovery of tiger and prey populations in key landscapes through active management/translocation.

- Promotion of policies for natural resource stewardship and conservation incentives.

- Mainstreaming tiger conservation into development actions for landscape functionality and connectivity.

- Significant reduction in illegal trade in tigers and their parts in source countries, and reduced demand for tiger derivatives in consumer countries.

- Strengthened transboundary collaboration for tiger, prey, and habitat conservation.

- Adoption of nature-based solutions for climate change adaptation and One Health approach for disease risk reduction.

You can read the full publication of the Global Tiger Recover Program 2.0 (2023-34) here.

The threats of the past remain while new challenges have arisen compounded by an annual funding gap of at least 138.477 million USD for priority tiger protected areas. It is undeniable that investment is needed from the Governments of the TRCs and from external parties to achieve the desired outcomes of GTRP 2.0. These resources will not only ensure the future of wild tigers across their range but would go a long way in helping to alleviate climate change, provide livelihood options to locals, sustain ecosystem services and prevent the spread of zoonoses.

You can contribute towards the future outcomes of the GTRP 2.0 by donating here.