- As the sixth mass extinction threatens global biodiversity, ensuring female representation is crucial for addressing this crisis effectively.

- By valuing both social and natural sciences equally and closing the gender representation gap, we can foster innovation and inclusivity in addressing multifaceted challenges like conservation.

- Listen to our podcast episode with Anna Klevtcova, recipient of the WildCats Conservation Alliance’s Professional Development Award. Anna shares insights on her interdisciplinary research, the challenges women face in academia, and the need for support in balancing research and family.

As we come face to face with our planets sixth mass extinction event, we must be able to respond quickly to safeguard global biodiversity. However, when we exclude half of humanity from the production of knowledge we lose out on potentially transformative insights. This can lead us to treating many of the world’s problems as unsolvable when really, we are just missing a female perspective. Therefore, we must increase female representation for us to be able to protect species on the brink of extinction.

Closing the female representation gap

Closing the female representation gap has profound benefits that extend far beyond women’s rights, exemplified by Daina Taimina. In just two hours, Taimina solved a century-old problem—physically representing hyperbolic space. A hyperbolic plane is a geometric opposite of a sphere curving away from itself at every point instead of in on itself. It is used in industry by statisticians, animators, and auto engineers. It is also the foundation for the theory of relativity and therefore the closest thing we have to an understanding of the shape of the universe. And yet, for hundreds of years, no one could physically model it. However, Taimina, a maths professor with a passion for crochet, realised in 1997 that she could make it out of yarn. Her creations are now the standard model for explaining hyperbolic space, revealing that closing gender gaps brings unique insights and impacts that may have been overlooked by men for centuries.

Taimina’s example demonstrates how including women’s perspectives when trying to find solutions to global problems such as biodiversity loss is vital now more than ever. We are currently witnessing an extinction rate that is 1,000 to 10,000 times faster than the historical natural rate posing a ‘wicked’ problem in conservation. The complexity of ecosystems, influenced by unpredictable dynamics and human behaviour, defies a simple solution. To address these multidimensional challenges, we need diverse perspectives, and only by closing the female and minority representation gap can we ensure transformational insights are contributed to both social and natural sciences.

Hard and soft sciences

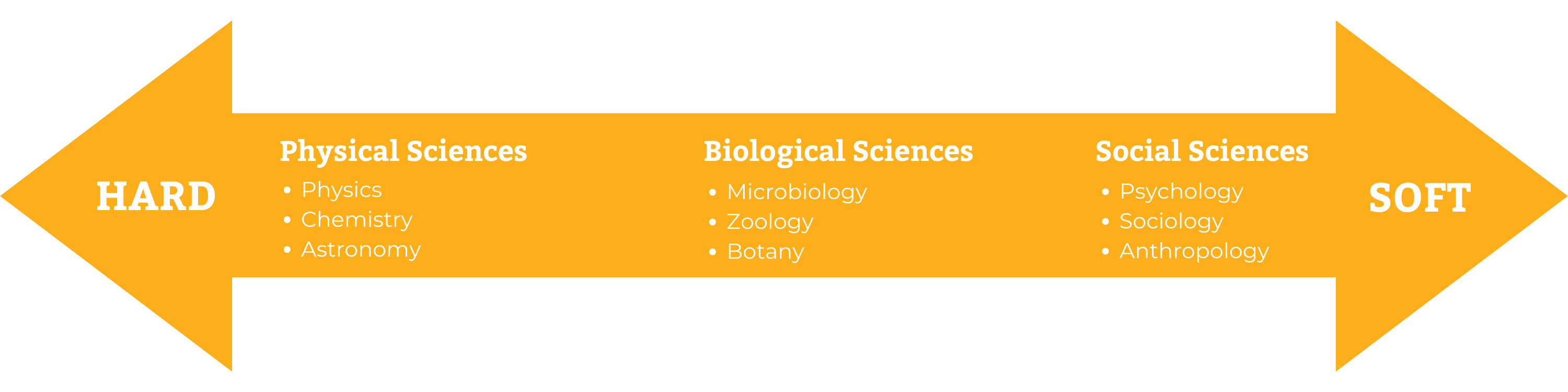

It is also imperative that we value both social and natural sciences equally which historically has not been the case. In the 19th century, the hierarchy of science concept was conceived, leading to the modern classification of scientific disciplines into hard and soft sciences in the 1960s. Hardness was defined in terms of the degree to which a field uses mathematics (hard) or empirical data (soft). This categorised natural sciences as hard and social sciences as soft. The hard and soft science metaphor has since been widely criticised for stigmatizing soft sciences, affecting public perception, funding, and recognition. Soft sciences, historically undervalued, were even considered pseudoscientific, leading to disproportionate funding cuts during the 2000s recession. Additionally, a gender bias exists, with a higher proportion of women in softer sciences, raising questions about the underlying causes and repercussions of this trend.

Can females ensure the future of felines?

To help get a better understanding of this value disparity and of being a woman in science we spoke to Anna Klevtcova, recipient of WildCats Conservation Alliance’s Professional Development Award. Anna has studied both hard and soft sciences and her current PhD looks at ecology through an interdisciplinary lens. Based in Russia, Anna holds degrees in geography and environmental management with geospatial science. She joined the Wildlife Conservation Society in 2018 and is currently focusing on the human dimensions of Amur tiger conservation in her PhD at the University of Florida, supported by WCS.